Today, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in Olivier v. City of Brandon, Mississippi, a case that presents fundamental questions about federal court access and the scope of constitutional protection under 42 U.S.C. § 1983. The question presented asks whether Heck v. Humphrey bars an individual who has already been prosecuted under a law from bringing a § 1983 action seeking prospective relief against future prosecutions for the same conduct.

The Legal Framework: § 1983 and Heck v. Humphrey

42 U.S.C. § 1983 serves as the primary vehicle for civil rights enforcement, authorizing suits against state and local officials for violations of federal constitutional rights. This Reconstruction-era statute enables individuals to seek both damages for past violations and prospective relief to prevent future constitutional harm.

Under Heck v. Humphrey, established by the Supreme Court in 1994, a person who has been convicted generally cannot recover damages on the theory that their conviction was unconstitutional unless that conviction has been overturned, reversed, or otherwise invalidated. The Heck doctrine serves to prevent § 1983 suits from undermining the finality of criminal convictions and creating inconsistent judgments between civil and criminal proceedings.

Gabriel Olivier’s Constitutional Challenge

Gabriel Olivier, an evangelical Christian who regularly engages in public preaching, encountered the constitutional issues at the heart of this case in Brandon, Mississippi. In 2019, the city enacted an ordinance restricting demonstrations to a specific area outside the Brandon Amphitheater, limiting protests to three hours before and one hour after live events at the venue.

In May 2021, after receiving a warning from police, Olivier continued preaching outside the designated “protest area.” He was subsequently charged with violating the ordinance, pleaded nolo contendere, and was sentenced to a fine and ten days imprisonment. Rather than appealing his conviction or seeking post-conviction relief, Olivier paid the fine and served his sentence.

Following his prosecution, Olivier filed a § 1983 lawsuit against the City of Brandon, arguing that the demonstration ordinance violated his First and Fourteenth Amendment rights both facially and as applied to his religious expression. Critically, Olivier sought only prospective relief, injunctive relief to prevent future enforcement of the ordinance and a declaratory judgment that the ordinance was unconstitutional. He did not seek damages related to his past prosecution.

The Fifth Circuit’s Problematic Extension of Heck

The Fifth Circuit extended Heck far beyond its traditional boundaries, concluding that a person like Gabriel Olivier, who has already been prosecuted once, intends to continue engaging in the same conduct, and faces a credible threat of future enforcement, cannot seek prospective relief to prevent future prosecutions. This interpretation represents a significant departure from Heck’s original scope and purpose.

The Fifth Circuit’s reasoning creates a logical inconsistency with both Heck itself and the fundamental structure of § 1983. Heck was designed to prevent civil suits that would undermine the validity of existing criminal convictions, particularly in the damages context where success would necessarily imply the invalidity of the conviction. But prospective relief operates differently, it seeks to prevent future constitutional violations rather than relitigate past criminal proceedings.

An individual with a history of past enforcement is not a speculative plaintiff seeking advisory opinions on hypothetical future scenarios. Instead, past prosecution provides the clearest possible evidence that future enforcement is reasonably likely. Gabriel Olivier’s situation exemplifies this principle: having been prosecuted once for his religious expression, he faces a concrete and particularized injury that is both actual and imminent under established standing doctrine.

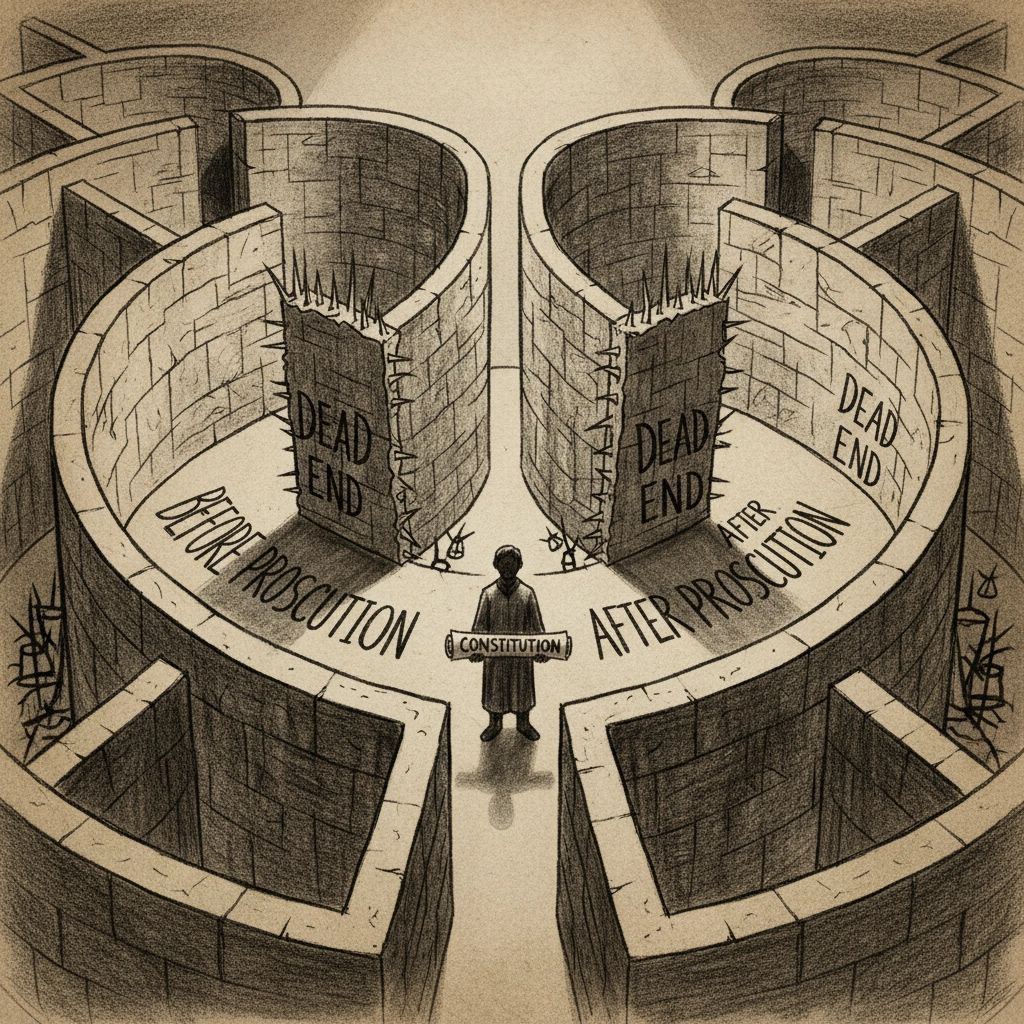

The Constitutional Dead Zone Problem

The practical effect of the Fifth Circuit’s approach creates what Judge Ho aptly characterized as a “constitutional dead zone”, a procedural trap that effectively shields unconstitutional laws from meaningful federal review. This creates a “heads I win, tails you lose” scenario for government enforcement:

Before any prosecution, the government routinely argues that the risk of enforcement is too speculative to establish Article III standing. Courts often dismiss these challenges as unripe, reasoning that no concrete injury has yet occurred and that enforcement remains hypothetical.

After a prosecution, under the Fifth Circuit’s reading of Heck, it becomes “too late” to seek relief because any constitutional challenge would necessarily imply the invalidity of the past conviction. This bars not only damages claims but also prospective relief designed to prevent identical future violations.

This procedural gamesmanship fundamentally misunderstands the purpose of both standing doctrine and the Heck rule. Standing requirements exist to ensure that federal courts decide actual cases and controversies, not to create insurmountable procedural barriers to constitutional review. Similarly, Heck exists to prevent inconsistent judgments and protect the finality of criminal convictions, not to immunize unconstitutional enforcement practices from prospective challenge.

The Doctrinal Disconnect

The Fifth Circuit’s extension of Heck creates several doctrinal problems that extend beyond this individual case:

First, it conflates damages claims with prospective relief claims, despite their fundamentally different legal purposes and effects. Damages claims necessarily look backward and require courts to determine whether past conduct violated constitutional rights. Prospective relief looks forward and seeks to prevent future violations through injunctive or declaratory relief.

Second, it transforms Heck from a rule about claim preclusion into a broader barrier to federal constitutional review. This exceeds Heck’s original purpose and creates tension with the broader civil rights enforcement scheme established by § 1983.

Third, it creates perverse incentives for both enforcement officials and affected individuals. Officials can effectively immunize enforcement practices by pursuing even minor prosecutions, while individuals face pressure to appeal or seek post-conviction relief for strategic civil rights purposes rather than based on the merits of their criminal cases.

Why This Case Matters for Constitutional Rights

Olivier v. City of Brandon presents the Supreme Court with an opportunity to clarify the proper scope of both Heck and § 1983 in a context that has significant implications for First Amendment rights and federal civil rights enforcement more broadly.

The case is particularly important for First Amendment challenges to laws restricting speech, assembly, and religious exercise. Many such challenges arise in precisely Olivier’s circumstances, individuals engaged in expressive conduct who face prosecution under potentially unconstitutional ordinances. If the Fifth Circuit’s approach were to prevail, it would create a significant gap in constitutional protection for core First Amendment activities.

More broadly, the case affects the balance between state sovereignty and federal constitutional protection. While federalism principles counsel against excessive federal interference in state criminal proceedings, they do not require federal courts to abdicate their constitutional role in protecting federal rights. The § 1983 framework reflects Congress’s judgment that federal court review remains necessary to vindicate constitutional rights that state systems may inadequately protect.

The Path Forward: Limiting Heck to Its Proper Scope

The Supreme Court should clarify that Heck v. Humphrey does not bar § 1983 claims seeking prospective relief against future prosecutions, particularly when the plaintiff has already been subjected to past enforcement and faces a credible threat of future violations.

Several doctrinal principles support this limitation:

Textual Analysis: Section 1983’s text creates a cause of action for constitutional violations, with no temporal limitation restricting it to pre-prosecution challenges. The statute’s broad remedial purpose supports allowing prospective relief even after past prosecution.

Standing Doctrine: Past enforcement provides optimal evidence of concrete and particularized injury, satisfying Article III requirements without the speculation inherent in pre-enforcement challenges.

Precedential Consistency: Limiting Heck to its original context: preventing civil damages claims that would undermine criminal convictions: preserves its core function without creating unnecessary barriers to prospective constitutional review.

Practical Necessity: Constitutional violations often involve ongoing enforcement practices rather than isolated incidents. Effective constitutional protection requires mechanisms for addressing systematic enforcement problems, not just individual prosecutions.

Broader Implications for Civil Rights Enforcement

The outcome in Olivier will significantly affect civil rights enforcement across multiple contexts beyond First Amendment cases. The principle at stake: whether individuals can seek prospective relief after experiencing enforcement under potentially unconstitutional laws: applies equally to:

- Fourth Amendment challenges to police practices and search policies

- Due process challenges to municipal enforcement procedures

- Equal protection challenges to discriminatory enforcement patterns

- Regulatory challenges to administrative enforcement schemes

A decision favoring the City of Brandon would create similar constitutional dead zones across these areas, effectively immunizing government enforcement practices from meaningful federal review once any prosecution has occurred.

Conclusion

Olivier v. City of Brandon, Mississippi presents the Supreme Court with a clear opportunity to prevent the transformation of Heck v. Humphrey from a targeted rule about criminal conviction finality into a broad barrier to constitutional review. Individuals who have already been targeted by enforcement under potentially unconstitutional laws should not be shut out of federal court when seeking to prevent identical future violations.

The Fifth Circuit’s approach creates precisely the type of procedural gamesmanship that § 1983 was designed to prevent. Past enforcement provides the strongest possible evidence of future enforcement likelihood, making previously prosecuted individuals the ideal plaintiffs for prospective relief claims rather than individuals who should be barred from court entirely.

Gabriel Olivier’s case exemplifies why this principle matters: having been prosecuted once for his religious expression, he faces ongoing enforcement under the same ordinance for identical future conduct. That concrete threat of future prosecution should open federal court doors, not close them. The Supreme Court should reverse the Fifth Circuit and restore § 1983 to its proper role as a meaningful vehicle for constitutional protection.

Rob Doar

Rob is a law and policy communicator who draws on experience from high-level appellate work, civil rights litigation, immigration matters, and daily criminal defense practice. His perspective is grounded in real cases and careful legal analysis, allowing him to explain complex issues with clarity and context.